From http://news.mongabay.com/2009/1130-indigenous_mapping.html

Rhett A. Butler, mongabay.com

November 29, 2009

A new handbook lays out the methodology for cultural mapping, providing

indigenous groups with a powerful tool for defending their land and

culture, while enabling them to benefit from some 21st century

advancements. Cultural mapping may also facilitate indigenous efforts

to win recognition and compensation under a proposed scheme to mitigate

climate change through forest conservation. The scheme—known as REDD

for reducing emissions from deforestation and degradation—will be a

central topic of discussion at next month’s climate talks in

Copenhagen, but concerns remain that it could fail to deliver benefits

to forest dwellers.

Much of the Amazon rainforest remains occupied by tribal

groups. While few of these live as conjured in the imagination, the

state of the forests in their territories is a testament to their

approach to managing lands. But like the Amazon itself, these groups

face new pressures from the outside world. For the indigenous, the lure

of urban culture is strong—cities seem to offer the promise of

affluence and the conveniences of an easy life. But in leaving their

forest homes indigenous peoples are usually met with a stark reality:

the skills that serve them so well in the forest don’t translate well

to an urban setting. The odds are stacked against them; they arrive

near the bottom of the social ladder, often not proficient in the

language and customs of city dwellers. The lucky ones may find work in

factories or as day laborers and security guards, but many eventually

return to the countryside. Some re-integrate into their villages,

others return in a completely different capacity than when they

departed. They may join the ranks of miners and loggers who trespass on

indigenous lands, ferreting out deals that pit members of the same

tribe against each other in order to exploit the resources they

steward. As tribes are fragmented, and forests fall, indigenous

culture—and the profound knowledge contained within—is lost. The world

is left a poorer place, culturally and biologically.

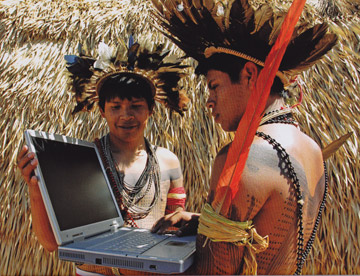

In Rondonia, Brazil, Surui use ACT-provided laptops to monitor their reserve using Google Earth technology. Photo © Fernando Bizerra Jr. |

But there is new hope, embodied by efforts to enable

tribes to become more self-reliant through the use of state-of-the-art

technology that builds on and leverages their traditional knowledge.

These tools can help them better defend their lands and offer the

potential for the next generation of Surui, Trio, or Ikpeng to have a

future of their determination rather than one dictated to them by a

society that values the resources locked in their territories over

their forest knowledge and rich cultural history. Through such

technology, tribes may be able to avoid a fate in which they become

destroyers, rather than protectors, of the basis of their culture—their

forest home.

At the forefront of this effort is the Amazon Conservation

Team (ACT), a Virginia-based group with field offices in Brazil,

Suriname, and Colombia. the Amazon Conservation Team has pioneered

geographic information system (GIS) training of indigenous groups in

the Amazon to enable them to map their land, not only as a means to

demarcate it and win title, but to catalog their cultural links to the

land. In building these “cultural maps,” tribes construct maps of their

territory that go beyond the topography of the terrain, capturing the

underlying richness of generations of human experience, including their

interaction with the land and other tribes, and the distribution of

plants and animals of nutritional, medicinal, and spiritual

significance. In other words, in as much as indigenous culture is a

product of the land, the maps capture the essence of these tribes.

But creating a cultural map is no easy task. It can take years

of work by the tribe, laying out what the map will contain, determining

what communities will participate, and coordinating who in the

community will do the actual footwork. Other considerations also come

into play, including harvesting cycles and seasons—mapping can’t

interfere with the ongoing the activities that sustain the tribe—and

the treatment of intellectual property contained in the maps, since

these can be used for nefarious purposes in the wrong hands, including

exploitation of timber, game, and medicinal plants.

A model map created by Indians in Brazil. Image courtesy of ACT. |

The training itself can also be complex. Indigenous

mappers must learn the ins and outs of handheld GPS units, GIS systems,

computers, and Internet tools like Google Earth before they can

construct maps and monitor their territories for threats and

encroachment. But the payoff can be well worth the effort: 20 groups in

the Brazilian Amazon have created culture and land use maps of their

territories. The maps include 7,500 indigenous names, 120 villages, and

thousands of area of cultural and historical significance. In Suriname,

the maps are being used to help indigenous groups get government

recognition of—and eventually title to—their lands. Some of the

indigenous mappers have gone on to become certified as park guards,

enabling them to earn an income while working to safeguard their lands.

The new handbook, “Methodology of Collaborative Cultural

Mapping,” walks readers through the process of establishing community

meetings between stakeholders, composing the mapping team, setting up

training workshops, conducting fieldwork, developing the map, and

finally delivering the map. The guide, which is available in both

English and Brazilian Portuguese, comes at an opportune time: interest

in tropical forest conservation has never been higher. The reason?

Tropical forests are seen as critical in combating climate change, both

in terms of their value in sequestering carbon and as a political

compromise that could serve as the developing world’s contribution to

reducing greenhouse gas emissions. As long-time stewards of tropical

forests, indigenous people are effectively forest carbon guardians. But

questions remain as to whether they will be recognized as such. Mapping

their lands may help indigenous groups demonstrate their critical role

in forest conservation efforts, earning them recognition, compensation,

and a stronger voice in determining how their resources are managed.

An example can be found in the Surui tribe’s carbon project in

Rondônia, Brazil, which aims to protect 250,000 hectares of forest.

Prior to establishing the carbon project , the Surui worked closely

with the Amazon Conservation Team to develop a cultural map of their

lands.

Indigenous park guards on patrol near Kwamalasamutu, Suriname. |

“The Surui ethno-graphic (cultural)

map has become the key instrument in integrating their traditional

knowledge of the forest with the latest technologies in carbon

measuring and monitoring,” Vasco van Roosmalen, director of the Amazon

Conservation Team-Brazil, told mongabay.com. “It is one of the key

instruments in translating the necessities of a carbon project to the

community and in ensuring that their perspectives are truly integrated

into the project design.”

Mark Plotkin, president of the Amazon Conservation Team, adds

that having completed their map, the Surui are much better positioned

to move ahead on their carbon credit project.

“After the mapping process has been completed, some of the

indigenous are trained as internationally accredited park

guards—meaning the forest protectors are in place, which is a real

hurdle for other carbon projects where nobody lives in and protects

these forests,” he told mongabay.com.

“Ethnographic mapping represents the perfect marriage of

ancient shamanic wisdom and 21st century technology,” Plotkin

continued. “When done right, it results in better protection of the

rainforest and enhanced capacity of the Indians to meet the

opportunities and challenges posed by the outside world.”