Sep 14th 2006 | OTTAWA

From The Economist print edition

Original story here: http://www.economist.com/world/la/displaystory.cfm?story_id=7911293

Yet another land-claim dispute turns ugly and shines a spotlight on the failure of Canada’s policies towards its aboriginal people

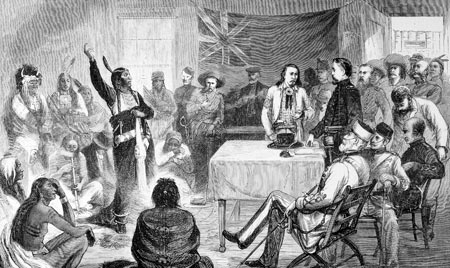

Corbis

CANADA’S much vaunted reputation for tolerance took a beating this summer in Caledonia, a town 80km (50 miles) south-west of Toronto, where a new housing development on land claimed by the Six Nations Iroquois Confederacy has sparked off a series of ugly clashes between the aboriginals and the town’s non-indigenous residents.

The land is part of a much larger tract given by the British to their Indian allies from New York in 1784 when members of the tribes fled to Canada after the American war of independence. Claiming that the land was thereafter sold without their proper consent, members ofthe Six Nations have been occupying the site for the past six months, setting up barricades and blocking traffic. This, in its turn, has provoked a series of counter-blockades, brawls, vandalism, and a fight with golf balls and stones. In a belated attempt to avert further violence, the provincial government bought the contested property from the private developers in June and opened negotiations with the Six Nations. But tensions in the town spiked again at the end of last month when the protesters threatened to complete the 11 unfinished homes themselves and to live in them throughout the winter.

Because Caledonia is (by Canadian standards) on the doorstep of Canada’s largest city, the conflict has been attracting blanket media coverage. But few have bothered to trace its origins back to their source: the spectacular failure of overall aboriginal policy. Treating their 1m indigenous citizens fairly should be the “ultimate moral issuefor Canadians”, says Paul Martin, the former Liberal prime minister. Instead, they are treated with a mixture of ignorance and indifference. The current policy, based on “white guilt and aboriginal anger”, does not work, argues John Richards of Simon Fraser University.

Canada’s current philosophical approach is a far cry from the 1969 attempt by Pierre Trudeau, another former prime minister, to assimilate the country’s aboriginals by abolishing separate Indian status and, with it, any right to special treatment by the state. Aboriginal anger forced Mr Trudeau to climb down. By 1982 he had had a change of heart, enshrining broad aboriginal rights in the new Canadian constitution. Assimilation as an official policy died, although it is still favoured by some academics, including Tom Flanagan of the University of Calgary, who has close ties to the current prime minister.

Yet few Canadians understand the special constitutional status of Canada’s aboriginals, comprising Indians, Métis, and Inuit, partly because it is still not fully spelled out in the constitution. The Indians believe they should deal with Canada on a government-to-government basis, just as their ancestors did in the 1700s, when the British bought peace in the colony by signing treaties guaranteeing Indian rights to land and self-government. Those were incorporated in the Royal Proclamation of 1763 and again in Canada’s new constitution. Paul Chartrand, a Métis member of a former royal commission on the aboriginals, says that Canadian governments are not interested in long-term solutions, seeking rather to “stamp out fires”. Mr Martin largely agrees: “This is a file that has been shoved under the rug for 150 years.”

The federal government spends an estimated C$9 billion ($8 billion) a year on aboriginal programmes, targeted mainly at the Indians living on 600-odd occupied reserves, where conditions are often dire. Last year the federal government had to evacuate the Kashechewan reserve in northern Ontario after its drinking water was found to be unsafe. The water quality in more than 200 other reserves has also been deemed risky. Although aboriginals living outside the reserves have lower levels of education, health and income than other Canadians, the gap is even wider for those on the reserves.

Meanwhile, disputes over land are frequent and often violent, the result of resurgent aboriginal nationalism and an awareness that the squeaky wheel gets the grease. Since 1990 some of the fiercest confrontations have been over an oil development near Lubicon Lake, Alberta, a golf course expansion at Oka, Quebec, a provincial park in Ipperwash, Ontario, a ski resort at Sun Peaks, British Columbia, and military flights over Labrador. Each has followed a depressingly similar course. Ownership is disputed. An aboriginal claim is filed and the federal claims-processing machinery grinds into motion. Years, often decades, go by without resolution. The fuse is lit when the contested activity is at last allowed to proceed, despite the outstanding claim. No matter which side eventually wins, the other regards it as an illegal occupation.

Not all the news is grim. On the land-claims front, there have been a number of cases where aboriginal insistence that their rights be recognised before industrial development proceeds has led to agreements on job creation, revenue-sharing, training and land ownership. This was the case with the Cree over the massive James Bay hydroelectric dams in northern Quebec, the Innu over the Voisey’s Bay nickel mine in Labrador, the Inuit over diamond mines in the Northwest Territories, and the 1999 creation of the new territory of Nunavut, the largest land-claim settlement in Canadian history. Now aboriginal groups along the path of the proposed Mackenzie Valley natural-gas pipeline in the Northwest Territories stand to become part-owners of the C$7 billion project—if it goes ahead.

“Large-scale resource development has been the catalyst for just about every major land-claim settlement across the country,” notes David Natcher, professor of aboriginal studies at Memorial University in Newfoundland. The bigger the development, the better the chance at settlement, he says, because the companies put pressure on governments to reach a deal.

But smaller disputes, like the one in Caledonia, are much harder to solve. The present confrontation is happening a full decade after a royal commission presented the federal government with a supposedly clear roadmap on how to repair its deteriorating relations with the aboriginals. Set up by the Conservatives following the 1990 Oka conflict, the commission reported to a Liberal government in 1996. But the Liberals largely ignored its recommendations, including the suggestion that land claims be settled by a tribunal composed of both aboriginal and non-aboriginal members, rather than by the courts.

It is not too late for the new government to dust off that report. But even if all the aboriginals’ claims are settled—and that seems unlikely given a backlog of more than 780 claims before the federal government—it would still not solve the aboriginals’ plight. Some analysts argue for much more to be done for the two-thirds of aboriginals living within Canadian society. That might tempt more Indians to leave the wretchedness of the reserves. But this would require the two levels of government to stop buck-passing and get their act together. Although the federal government is supposedly responsible for the aboriginals’ overall welfare, the provinces have jurisdiction over land and resources.

Is the new Conservative government ready to change decades of failed policies? Early signs are mixed. As a one-time member of a federal claims commission, Jim Prentice, the new minister of Indian and northern affairs, has wide experience of aboriginal affairs. He has already pledged to slash the backlog of claims and to do more for the off-reserve aboriginals. The government has also agreed to honour the promise of $2.2 billion by the previous government to compensate the victims of abuse in aboriginal residential schools. But other moves seem less promising: Mr Prentice has declined to intervene in Caledonia, refused to support a UN declaration on indigenous rights and reneged on the last government’s pledge of an extra C$5 billion for social schemes.

As with so many federal issues in Canada, any real change in policy is unlikely until there is a majority government with the strength and will to ram it through. Meanwhile, private firms push ever further into remote areas in search of lumber, minerals, oil and gas, creating a whole new series of potential flashpoints.

Copyright © The Economist Newspaper Limited 2006. All rights reserved.